F23: Week 4—Exploring EndNote

- Casey Wolf

- Sep 16, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Oct 10, 2023

As I finish up the Standard List, we are beginning to encode the EndNote fields onto the database. With the Pemberton Papers as the pilot digitized collection for PRINT, we implemented a documented process to encode metadata onto digital records. EndNote was selected for its accessibility and extendability. Able to import and export CSV files, EndNote encoding provides an accessible way to create and export data across partner institutions. Not only is the data accessible, but it is also approachable from a team member perspective. As a highly collaborative project with a public history focus, PRINT requires user-friendly methods to encourage and support engaged interaction with the documents. Adopting DH practices with the user in mind is more likely to sustain and maintain participation in the project.

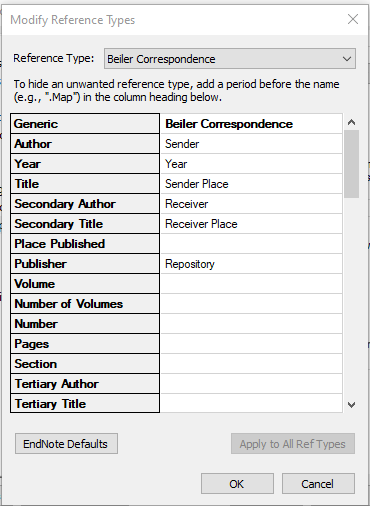

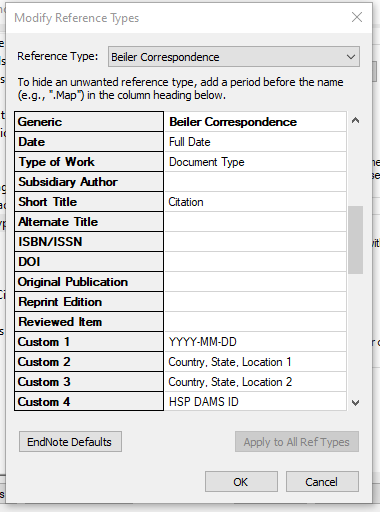

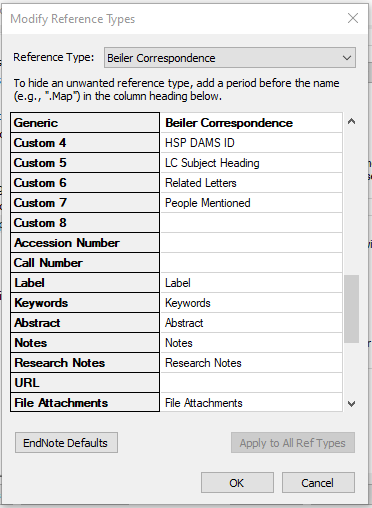

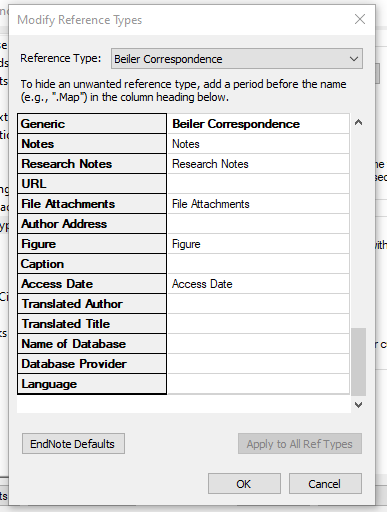

Beyond EndNote’s ability to import and export data, it also supports customized metadata fields. While some fields are standardized, the metadata field list—defined as Reference Type in the program—supports changing the headers displayed to define the fields. The customizable aspect of the field list supports metadata entry requested by partner institutions and renaming the display field name allows for a more specific approach to data description. Establishing the Reference Type “Beiler Correspondence” creates an importable and exportable schema for describing data across project teams. This ensures that all project team members follow an outlined standardized practice of encoding metadata across collections.

The first image shows the library of collection records on the left, with the individual record displayed on the right. The images following show the individual record: how the fields describe the record, and how the metadata is encoded within the fields.

By importing the Reference Type schema, all EndNote instances across project teams become standardized and allow the same set of fields to apply across datasets. With a wide variety of researchers made available to the project through an NHPRC grant, all data processing needs to be applicable to the records it is describing, while also approachable by users with different backgrounds of technical knowledge. Additionally, exporting the Reference Type and uploading it to the project repository/cloud drive allows for long term storage and reimplementation of established standards when incorporating new collections into the project.

The images above illustrate how the Reference Type is set up and how the fields can be described. Many serve a PRINT-specific function that can be converted into machine-readable category, once the language is established that allows the computer to communicate between the data and the database. Part of establishing that language is determining and documenting how that information is encoded within the fields by the project team. Not only do the fields require standardization, but the format in which the fields are populated requires it as well for optimal utilization of data for the project. As such, much of our meeting time this week was dedicated to clarifying these standards as we prepare for the project teams to begin data entry within their separate EndNote databases.

To ensure the input of data is standardized across collections, we are clarifying them both for the user and the computer. While I am responsible for the former, Dr. Brook Miller is working on the latter. My project piece involves creating a document to instruct users in encoding expectations: outlining the proper field for relevant data, and clarifying how it is meant to be input. From an internal standpoint, our meetings ensure we both have a clear understanding of how the data is describing the records and how the data should be “read” by the computer. It also provides an opportunity to mitigate any potential issues users might encounter when encoding the metadata. This part of the process is crucial to prevent issues with the data and encoding that might lessen its inefficiency. Such meetings are a crucial element of DH practice, which brings together people of different academic and educational backgrounds to present new ways of viewing historical inquiry and methods. They are also a welcome opportunity to view data, sources, and other project elements in new ways—either by learning new information and skills, or seeing elements from a different perspective.

Comments