Week 13—Club 436 and Connecting the Construction of Community

- Casey Wolf

- Apr 15, 2022

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 14, 2023

This week, I wanted to follow and wrap up some research threads:

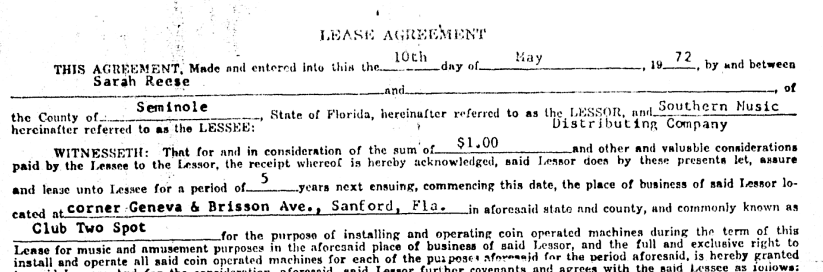

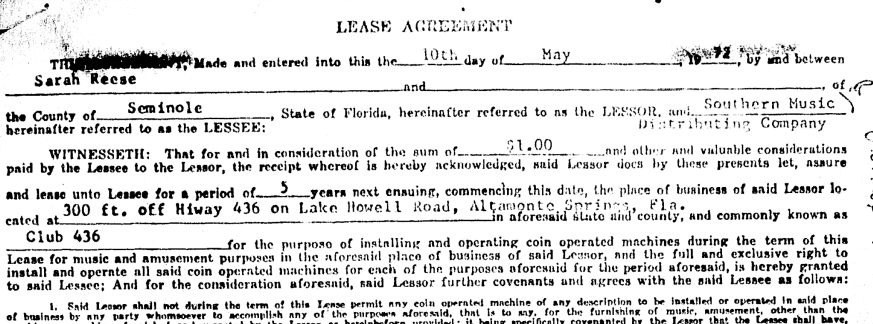

While searching for the location of Clayton Thomas’ 2 Spot, I found a lease agreement from May 1972 which two parties previously unknown to me—Sarah Reese and the Southern Music Distributing Company. Searching for the name “Sarah Reese,” I found another lease agreement between the same parties on the same date but for a different property—Club 436. Further research into the Southern Music Distributing Company is warranted as its presence on these documents presents an intriguing potential connection to the Circuit or to African American music scenes of the time.

In the document, the address is given as "300 ft. off Hiway 436 on Lake Howell Road." Putting “Highway 436 and Lake Howell Road” into Google Maps returns the location in the following picture.

Seeking to narrow down the exact location, I did some further digging and came across two pieces of information: a Reddit post on the "Orlando" board and a February 15, 2004 Orlando Sentinel article. Attempting to recall the name of the site, the user mentions its approximate location and provides a few clues, namely "on 436, right over 17-92," "on your way to Altamonte," and "across from the McDonald's at the bend." The Orlando Sentinel article gives the address of a Club 436 as "110 Anchor Road, near State Road 436" and "just east of Altamonte." Inputting 110 Anchor Road on Google Maps returns the following results. In the map image, we can see the site located near a McDonald's on State Road 436 with US 17-92 nearby. Altamonte Springs is not shown but it is located to the left.

Turning to Street View, we can see a vacant property with boarded up windows. However, signage around its roof indicates that it was a former Cocktail Lounge and Bar. Going back to 2008 on Street View, we can see a canopy on the side of the building, confirming it was at one time named Club 436. Given that we have seen a "name bank" of commonly used names for sites across the state and country, it is entirely possible that there were two similarly named venues--that this Club 436 was different from Clayton Thomas'.

To further confirm this as Clayton Thomas' Club 436, I then sought to connect the transfer of ownership between Thomas and Reese. With our warranty deed from last week documenting a transfer of ownership from Clayton Thomas to Bertha Thomas, I searched for Bertha Thomas and Sarah Reese. I found a transfer of property between the two. Again, the document identifies Club 436 as several lots on Blocks 3 and 6 of the Lakeview Subdivision. Unlike last time, a few of the street names (Amanda and Brewer) remain the same, allowing us to overlay the Lakeview plat map onto the modern landscape. By cross-referencing documents in this way, we can see the two locations match!

In Week 11, I discussed accommodations and how narratives around them are reflective of the lived experiences of African Americans in Jim Crow Florida. While looking further into the South Street Casino and the hotel built by Dr. William Monroe Wells, I did not expect to find such a variety of events and entertainment opportunities hosted at the site. Finding these events within the historical record, it is evident such sites speak of Black entrepreneurship, entertainment, and community.

Just as they provided social gathering and entertainment opportunities, these sites functioned as fundraising venues to boost or supplement funding to Black communities and organizations, historically shut out of economic opportunity or stimulus. Usually these events included musical entertainment, often by Circuit performers. To purchase insurance and fire equipment, the Midway and Canaan City Volunteer Firemen's Department held an event at the Deluxe Bar which featured a performance by Bobby Williams and his Mar-Kings—a quintessentially Floridian act with Williams hailing from Orlando and featured on an album entitled Florida Funk: Tales from the Alligator State.

Organizations that used Club Eaton as a fundraising venue include the following:

AmVets hosted the I Want to Do It Dance to raise money for veterans

Moderneers Club held the annual Harvest Roundup Ball to raise money for a charity for the intellectually disabled

Bridgedette Club sponsored a benefit dance, featuring music by the Balladiers, for the hospital on October 31, 1958

Organizations that used the South Street Casino, located in Parramore, include

Recreation Department music specialist George L. Johnson in partnership with Jones High School organized a music institute—holding music lessons and chorus performances "to stimulate interest and musical expression among the negro population of Orlando."

Girl Scouts who held a Spotlight Show

Shriners along with the Negro Chamber of Commerce

Orlando Food Handlers School held a certification course to provide education and better opportunity for employment

Delta Sigma Theta Sorority hosted Queen of Hearts dance featuring Five Royales with Jimmie Cole

Mid-Summer Ball featuring performances by Choker Campbell Orchestra and Big Joe Turner on June 11, 1956

March of Dimes held a President’s Ball with use of the venue donated and featuring entertainment from Jesse Price and his Orchestra

Different clubs organized a "Get Acquainted" party for the benefit of Black soldiers and their wives stationed at the Orlando Air Force Base

Negro Chamber of Commerce hosted a rally and speech event for local political candidates

Constructing and preserving site narratives can contribute to the preservation of African American experiences in Jim Crow Florida. Additionally, these narratives reveal more information about African American performers—often Circuit entertainers. By searching records, researchers can locate and place these experiences onto the current landscape. Using archival records can contribute to site narratives by presenting insightful information but they do require support. Such interpretations of sources are a single perspective and, as demonstrated over the course of this blog, often adrift without a vital source of knowledge—those who have memory of them. As such, efforts to locate local knowledge, construct site narratives, and document the history of the Chitlin’ Circuit need to connect to other networks and similar projects.

Digital tools are instrumental in organizing and conceptualizing research, especially in public history contexts. However, those I have implemented thus far do not connect to networks of scholarship. Fortunately, digital history creates opportunities to publish online to facilitate these connections. Online publication also ensures research and interpretations are more accessible to wider audiences, often by using different and more dynamic tools for presentation. Given that this project relies heavily on the collection of local history and the collation of sources from a variety of archives to place the sites in space, the creation of a digital exhibit—such as those on RICHES—where interpretation can combine with the presentation of sources, images, and locations might be a promising method of publication for access by both the public and other researchers.

Comments